by: Dustin Hixenbaugh

Once a father and mother took their son to a preacher with the hope that this man who had baptized their children with his own hands would provide a cure for their son’s unimaginable impulses—for his attraction to men. After hearing the parents out, the preacher replied that he had known the young man his entire life, that he had developed a great faith in his character, and that he could not condemn him for following his heart. In his view, it was the parents, not the son, who needed “curing,” for it was they who had allowed the fear of the unknown to come between them and one of their children.

This is a story that I read a long time ago in one of the issues of The Reader’s Digest or Guidepoststhat my own parents stacked in their bathroom. But I found myself retelling it a couple of weeks ago in front of a crowd of teachers in a presentation on “Supporting LGBTQIA+ Students” at the University of Houston. Of course, a lot has changed since I read the story in the late 1990s, and arguably gay, lesbian, and bisexual teens are better represented today in popular culture and more accepted by family members, teachers, and peers, than they ever have been. Unfortunately, the same cannot be said for teens who are, or who may be perceived as, transgender—a term that distinguishes people who claim a gender identity that does not correspond to the gender they were assigned at birth. Trans children, who are bullied at schooland smeared on social media, are in desperate need of adults who will stand up for them the way the preacher stood up for that young member of his congregation.

At this point, I should clarify that my intention in this post is not to convince you that trans children exist or that you should “approve” of them. The former is a demonstrable fact—1.04% of West Virginians between the ages of 13 and 17 identify as transgender, according to a studyby UCLA’s Williams Institute—and the latter, your approval, is beside the point. As far as I’m concerned, a teacher’s job is not to tell students who they are, but rather to make space for students to discover who they are and to develop the skills and mindsets they need to be their best selves. Moreover, trans students’ unique needs require that teachers do more than turn a blind eye and wish them the best. Research suggests that trans students feel unsafe in schools and earn lower GPAs than their cisgender peers unless school personnel take deliberate steps to help them feel welcome and secure.

So, what can you do to foster a welcoming environment for the trans students you will almost certainly teach? Here are five fairly easy suggestions:

1. Let students introduce themselves. It’s the first day of school and you’re gazing upon a sea of unfamiliar faces. Do you take attendance by calling names off a roster? Or do you ask students to give their names to you? For many teachers, this is a six-of-one-half-a-dozen-of-the-other decision, but for students who are transitioning between genders and who may be using names that are different from the ones printed on their official school records, it can be a source of anxiety and embarrassment. My advice? Ask students to introduce themselves to the class using the names they prefer, and if you can’t match a student’s preferred name to the one that appears on your roster, ask them about it privately. Better to screw up attendance on the first day of school than set a student up for humiliation for the entire year.

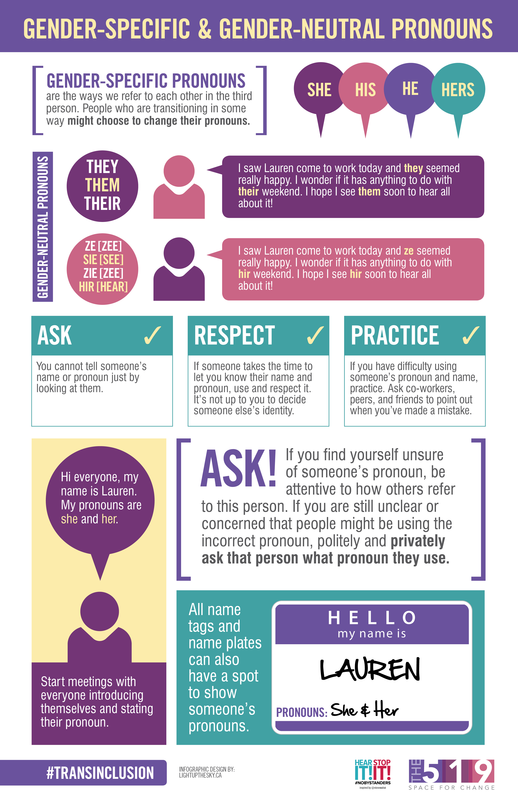

2. Embrace gender-inclusive language. On the one hand, this means avoiding phrases like “you guys” and “ladies and gentlemen,” which assume that the people you’re addressing identify with the gender(s) implied in your words. I spent ten years in Texas and have grown to appreciate “y’all” as an inclusive alternative, but you may find another phrase (“folks,” “friends,” and so forth) that you like better.

On the other hand, embracing gender-inclusive language also means accepting “plural” pronouns (they, them, their) in the place of gender-specific “singular” pronouns (he, him, his; she, her, hers). If you’re a grammar stickler, you may be loathe to allow a student to write a sentence like, “My friend Mary invited me over to their house.” But English thrives as a world language because it is constantly evolving, and, if you think about it, the sentence is entirely accurate if your friend Mary is trans or gender non-conforming.

3. Educate yourself. Make an effort to learn about the lives trans teens lead in- and outside of the schoolhouse. You can start by tuning into the TLC reality series I Am Jazz, about a young trans woman who is navigating high school and looking forward to gender reassignment surgery. You can also track legislative efforts to protect/curtail trans rights. Lately, battles over trans rights have centered around state and local “bathroom bills” that would require individuals to use public bathrooms that correspond to the sex on their birth certificates, disregarding the damage such policies inflict upon trans people. West Virginia does not offer any statewide protections for trans people, and although some cities have passed their own protections, others, like Parkersburg, have given in to opposition from anti-trans activists.4. Educate your students. Even if you never teach a trans student, you will teach plenty of students who will interact with trans people in college, on the job, etc., and don’t you want them to handle those interactions well? Consider integrating into your curriculum and classroom library texts that affirm the humanity of trans people and give some context to the challenges they face. My favorite book is Susan Kuklin’s Lambda award-winning Beyond Magenta, which features the personal stories of a culturally diverse group of teens as well as a stunning collection of photos. But you have many options. Alex Gino’s George and Jacqueline Woodsen’s “Trev” (anthologized in How Beautiful the Ordinary) are appropriate for middle schoolers, while Julie Anne Peters’ Luna, Ellen Wittlinger’s Parrotfish, Cris Beam’s I Am J, David Levithan’s Two Boys Kissing, and Meredith Russo’s If I Was Your Girl appeal to the YA crowd.

5. Have your trans students’ backs. Someday, you might find yourself sitting down at a table with parents who oppose their child’s desire to wear different clothes or adopt different pronouns. Even if you regret these parents’ circumstances, I beg you not to join an effort to redirect a child’s gender expression. Rather, please put yourself in the position of advocate, like the preacher I described at the top of this post.

“I can see that your family is under a lot of pressure right now,” you might say to these parents. “And while I cannot tell you how to parent your child, I can assure you that kids who identify as transgender do grow up to be great human beings and productive members of society. More importantly, I know your child well, have great faith in their character, and know that they would not do anything to hurt you. I encourage you to approach your child with an open heart and mind.”

In a world where 30% of trans kids attempt suicide, words such as these, spoken with love from a teacher, have the power to save lives.

How does your school or district support LGBTQ+ students? What are some ways schools and teachers in West Virginia can provide better support for trans students? How can schools help teachers to better understand the needs of LGBTQ+ students?